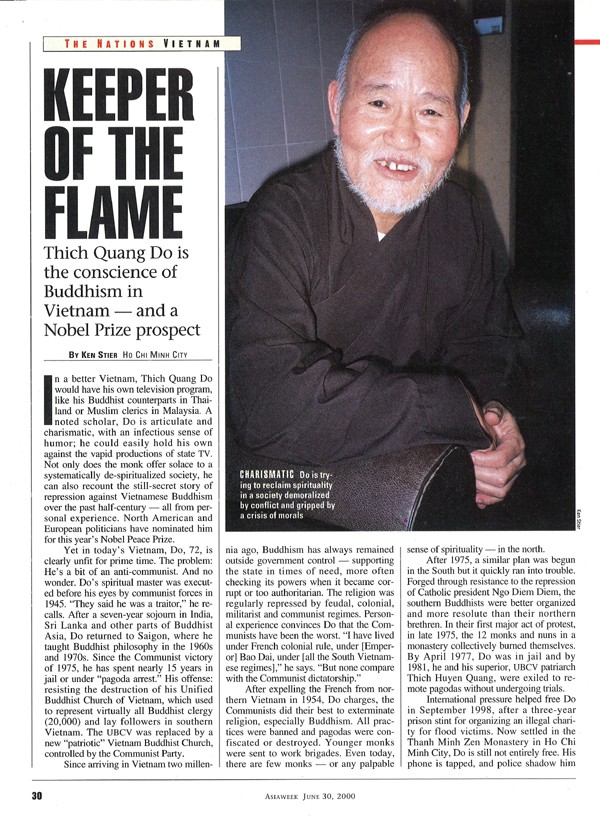

Venerable THÍCH QUẢNG ĐỘ, secular name Đặng Phúc Tuệ, was the Fifth Supreme Patriarch of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam and a leading advocate of religious freedom, human rights and democracy in Vietnam. Sixteen times nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, he won worldwide recognition for his non-violent actions for freedom in Vietnam. His refusal to be silenced by intimidation, imprisonment and internal exile for over four decades has inspired Vietnamese of all generations.

Thích Quảng Độ was the first person to forge links of solidarity between dissidents from the north and south, thus bridging a decades-long geographical and ideological divide. He was also an eminent scholar, former lecturer in oriental philosophy and Buddhist studies, and well-known writer, with over a dozen published works including novels, poetry, translations and studies of Vietnamese Buddhism.

Thích Quảng Độ was born on 27 November 1928 in Thanh Châu village in Thài Bình province (northern Vietnam). He became a monk at the age of 14. In 1945, when he was just 17, he witnessed the summary execution of his religious master by a revolutionary People’s Tribunal. “At that precise moment”, wrote Thích Quảng Độ in an Open letter to Communist Party Secretary-general Đỗ Mười in 1994, “I vowed to combat fanaticism and intolerance in all its forms, and devote my life to the pursuit of justice through the Buddhist teachings of non-violence, tolerance and compassion. I have never regretted this decision. But little did I realise how this simple vow would lead me down a path paved with prison cells, torture, internal exile and detention for so many years. I soon learned that all tyrants fear the truth, and one must be ready to pay the price – sometimes a very high price – to defend the convictions and values one believes to be right”.

An outstanding scholar and talented writer, from 1951-1957, Thích Quảng Độ spent 6 years as a Research Fellow of Buddhist and Indian philosophy at several universities in Sri Lanka and India, including the Vishava Bharati University in Santiniteketan, Bengal. During the 1960-70s, he was Professor of Oriental Philosophy and Buddhist Studies at Vạn Hạnh Buddhist University (Saigon), the Faculty of Letters of Saigon University and the Hòa Hảo Buddhist University in Can Tho. In 1971-72, he taught Buddhist studies at the Pontifical College Pius X in Dalat. Despite his exile and banishment by the communist authorities in 1982, his scholarship and vision earned him widespread respect, even in Communist Party circles. In the official magazine Văn Học (Literary Studies, No 4, Hanoi, July- August 1992), Thích Quảng Độ is highly praised for his wisdom and extensive knowledge by a communist scholar who visited him during his years in internal exile in Vu Doai.

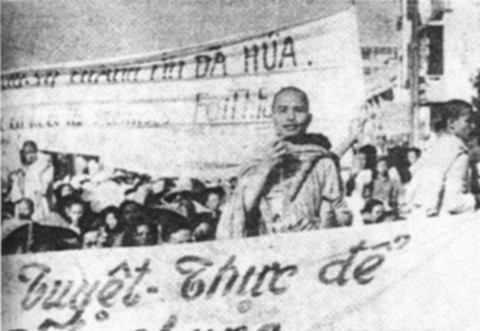

Thích Quảng Độ’s convictions led him to oppose authoritarianism under different political regimes. After Vietnam was partitioned by the 1954 Geneva Agreement, he became a prominent figure in the protest movement against the anti-Buddhist policies of the Ngô Dình Diệm regime in the South. On the night of 20 August 1963, he was arrested along with thousands of Buddhists in a massive Police sweep launched by the Diem government in Hue and Saigon. Thích Quảng Độ was brutally tortured. Yet he continued resistance in prison, secretly translating articles from the international press on the Buddhist struggle which were smuggled in by Buddhists with his meals. Released after the fall of the Diem regime on 1st November, Thích Quảng Độ’s health was seriously damaged by the brutal torture. He suffered from tuberculosis for three years, and was sent to Japan in 1966 for a lung operation. Before returning to Vietnam, he spent two years travelling and studying in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand and Burma.

After the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV) regained its legitimate status in 1964, Thích Quảng Độ was appointed UBCV Spokesman and Inspector of the UBCV’s Executive Institute (Viện Hóa Đạo, the Institute for the Dissemination of the Dharma) in 1972. He became the Institute’sSecretary-general in 1974. Throughout the Vietnam War, along with other UBCV leaders, Thích Quảng Độ took an active stance in favour of peace.

After the Communists took power in 1975, a fierce campaign to suppress Buddhism was launched in South Vietnam. UBCV property was confiscated, its institutions dismantled, thousands of monks were arrested or forcibly drafted into the army. As the UBCV Secretary-general, Thích Quảng Độ sent thousands of letters to the authorities protesting specific cases of religious repression. All copies of the letters were destroyed in July 1982 when Police seized the UBCV’s headquarters at Ấn Quang Pagoda. It took 5 days to burn the UBCV’s documents and files.

Tension reached a climax on 3rd March 1977, when Police attacked and seized the Quách Thị Trang orphanage in Saigon. That day, Thích Quảng Độ signed a Communiqué summoning all Buddhists to prepare for a non-violent struggle to defend the UBCV and protect religious freedom. This led to his arrest in April 1977, along with Thích Huyền Quang and several UBCV leaders on charges of “anti-revolutionary activities” and “undermining national solidarity”. Thích Quảng Độ was detained in solitary confinement in Phan Dang Luu Prison for 20 months. Following international pressure, he was released after a brief trial on 10th December 1978. The same year, Thích Huyền Quang and Thích Quảng Độ were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Irish laureates Betty Williams and Mairead Maguire.

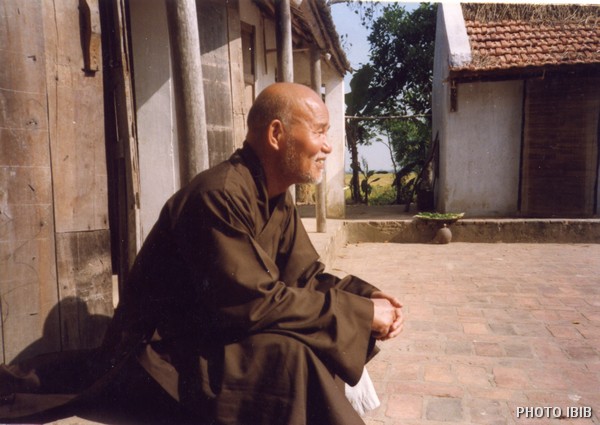

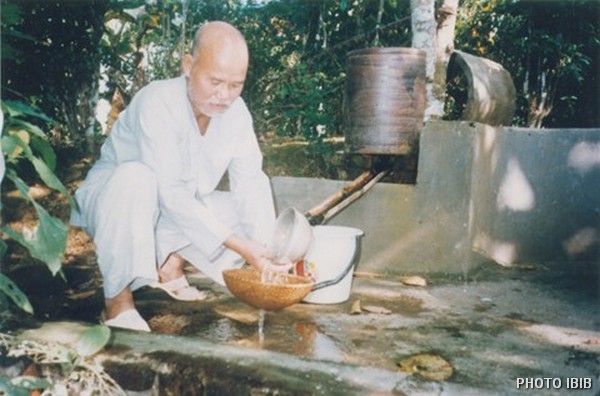

On 25th February 1982, Thích Quảng Độ was again arrested for opposing the creation of the State-sponsored “Vietnam Buddhist Church”, an organization controlled by the Communist Party’s “Vietnam Fatherland Front”, and for resisting efforts to make the UBCV join this State-run body. He was sent into internal exile in the remote village of Vũ Đòai in Thái Bình Province (northern Vietnam), where he spent 10 years under house arrest. The only reason given for detention was “by carrying out religious activities, you are ipso facto engaged in political activities”. His 84-year-old mother was exiled with him. She died in 1985 from malnutrition and lack of medical care. In 1990, the Minister of Public Security Mai Chí Thọ, one of the regime’s most powerful figures, invited Thích Quảng Độ to take up a post in the State-sponsored Vietnam Buddhist Church in Hanoi. Thích Quảng Độ refused.

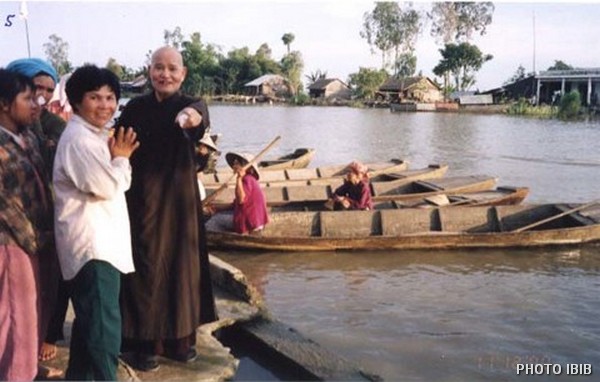

In 1992, Thích Quảng Độ broke out of internal exile and went back to the Thanh Minh Zen Monastery in Saigon. Shocked by the government’s widespread campaign to suppress the UBCV, in August 1994, Thích Quảng Độ set up a sign on his Monastery inscribed “Exiled Secretariat of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam” and called on Buddhists all over the country to restore UBCV nameplates torn down by the Communist authorities. The same year, he sent an Open Letter to VCP Secretary-general Đỗ Mười along with a 44-page document entitled “Observations on the grave offences committed by the Vietnamese Communist Party against the Vietnamese people and against Buddhism”, detailing persecution against Buddhism since 1945. A copy was smuggled to the UBCV’s International Spokesman in Paris, Võ Văn Ái, requesting that he publish it within 6 months if the government made no reply. In 1994, Thích Quảng Độ also began organizing the UBCV’s activities, mounting a rescue mission for victims of disastrous floods in the Mekong Delta which had left 500,000 people homeless. This was the very first public UBCV mission since the church was banned in 1981. Police intercepted the UBCV convoy as it prepared to leave Saigon on 5 November 1994, confiscated all relief aid and arrested the organizers. Thích Quảng Độ was arrested on January 4, 1995. He was put on trial as a “Vietnamese delinquent”, not as a Buddhist monk.

For these “crimes”, on August 15, 1995, Thích Quảng Độ was sentenced to 5 years in prison and 5 years house arrest on charges of “sabotaging national solidarity” and “taking advantage of democratic freedoms to violate the interests of the State and social organizations”. Initially detained in Ba Sao Camp, he was transferred to the notorious B14 Prison near Hanoi, one of Vietnam’s harshest prisons. Thích Quảng Độ’s health deteriorated due to harsh conditions and lack of medical care.

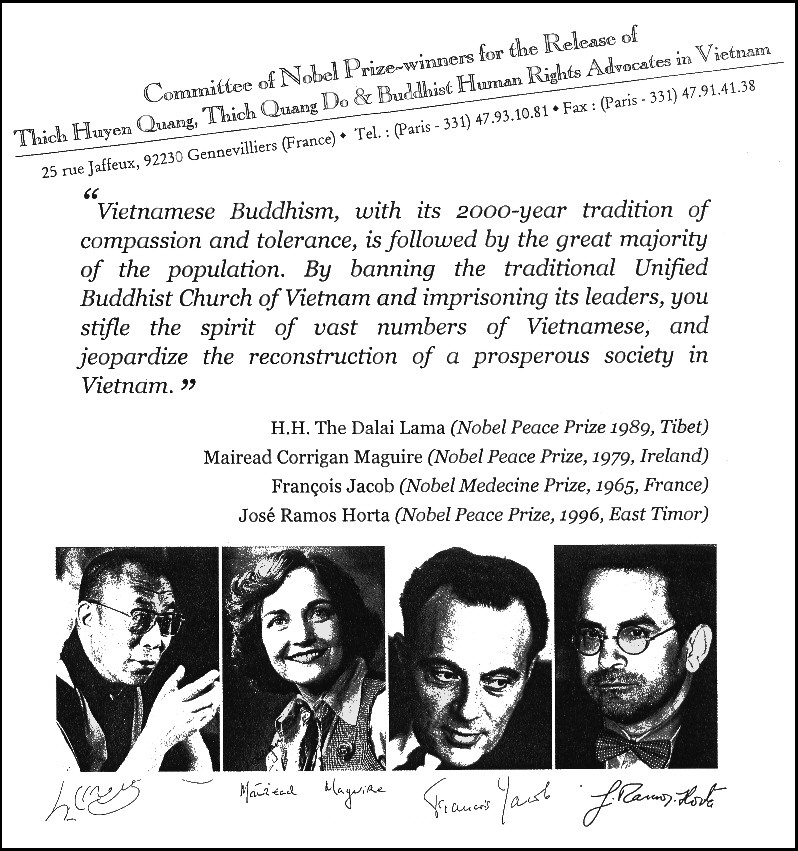

Thích Quảng Độ’s arrest sparked off strong international protests among human rights groups across the globe. Four Nobel Prize Winners (HH the Dalai Lama, José Ramos-Horta, Mairead Corrigan Maguire and François Jacob) formed a support committee for his release. The then US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright also demanded his unconditional release.

As a result, Thích Quảng Độ was released in a government amnesty on 2nd September 1998. He returned to the Thanh Minh Zen Monastery in Saigon, but was placed under house arrest and strict Police surveillance, with his phone cut and all visits monitored – “I have left a small prison only to come into a larger one”, he said. In October 1998, the UN Special Rapporteur on Religious Intolerance, Abdelfattah Amor was physically impeded from visiting Thích Quảng Độ by Security Police. Despite these restrictions, Thích Quảng Độ continued his peaceful combat by writing appeals in a spirit of dialogue to the Vietnamese leadership for the respect of human rights, the release of prisoners of conscience, the abolition of the death penalty, and national reconciliation between Vietnamese of all different opinions. He also pursued his efforts to draw international attention to the human rights situation in Vietnam, writing letters to the European Union with a list of 31 political prisoners in 1999, to the US Congress etc.

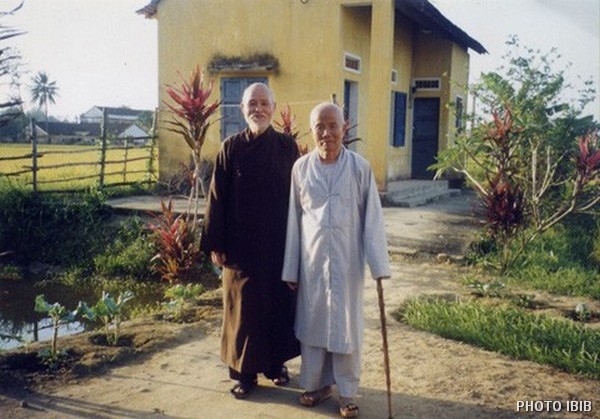

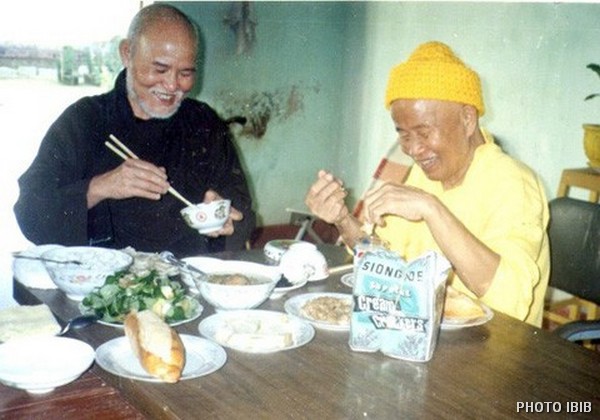

In 1999, Thích Quảng Độ was appointed President of the UBCV’s Institute for the Dissemination of the Dharma (Viện Hoá Đạo), thus becoming the second-ranking UBCV dignitary after the Patriarch Thích Huyền Quang.

In the following years, Thích Quảng Độ worked tirelessly to organise UBCV welfare, social and humanitarian programmes to promote social justice and aid people in need. In 2000, he personally led a relief mission to aid flood victims in the Mekong Delta. These efforts brought him renewed arrests, interrogations, harassment and accusations of “violating national security”. He also made frequent attempts to visit the Patriarch Thích Huyền Quang, under house arrest in Quảng Ngãi and Bình Định, but was systematically intercepted. In 2006, he was arrested as he tried to board a train to make a New Year visit to the Patriarch, and released only after 40 UBCV monks staged a hunger strike on the station platform.

On February 21st 2001, confronted with the impossibility of any dialogue with the Vietnamese authorities, Thích Quảng Độ launched an “Appeal for Democracy in Vietnam”, calling on Vietnamese from all political and religious families to rally together arounda radical 8-point transition plan for democratic change. The Appeal received overwhelming support, with endorsements of over 300,000 Vietnamese, and over 200 MEPs, Members of the US Congress and international personalities. The government reacted by sentencing Thích Quảng Độ (without trial) to two years “administrative detention” on June 1st 2001. He was detained incommunicado at theThanh Minh Zen Monastery, deprived even of medical treatment for his diabetes and high blood pressure. Euro-MP Olivier Dupuis staged a demonstration outside the Monastery in protest on June 6th 2001. He was arrested and expelled from Vietnam.

Released on June 27th 2003 as a result of concerted international pressure, Thích Quảng Độ was arrested again along with Thích Huyền Quang and several other UBCV leaders on October 8th 2003 after he participated in the UBCV Assembly convened by Patriarch Thích Huyền Quang to elect a new UBCV leadership. Thích Quảng Độ and Thích Huyền Quang were never formally charged, but were accused of “possessing state secrets” – an offence which carries the death penalty in Vietnam – and placed under strict surveillance at their respective monasteries. The US Congress and European Parliament adopted simultaneous Resolutions condemning the crackdown and calling for the immediate release of the new UBCV leadership.

In 2005, marking the 30th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War and the 30 years of the UBCV’s movement for religious freedom, democracy and human rights, Thích Quảng Độ launched two vibrant appeals to the international community and the people of Vietnam. In a video message addressed to the United Nations in April 2005, he argued that even economic development was untenable without democracy and freedom:

“What can we do to bring stability, well-being and development to the people of Vietnam? During my long years in detention, I have thought deeply, and I have come to the conclusion that there is only one way – we must have true freedom and democracy. We must have pluralism, the right to hold free elections, to choose our own political system, to enjoy democratic freedoms – in brief, the right to shape our own future, and the destiny of our nation. Without democracy and pluralism, we cannot combat poverty and injustice, nor bring true development and progress to our people. Without democracy and pluralism, we cannot guarantee human rights, for human rights cannot be protected without the safeguards of democratic institutions and the rule of law”.

Police seized the video and arrested the young monk who filmed it. However, the UBCV network managed to smuggle out an audio version, which was shown by Võ Văn Ái at the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva in April 2005.

Thích Quảng Độ’s “New Year’s Letter for Pluralism and Democracy” (February 2005) was an unprecedented call for unity, and it represented a turning point in Vietnam’s democracy movement. Addressed to Vietnamese Communist Party and military veterans, academics close to the VCP, human rights defenders, cyber-dissidents and democracy activists from all walks of life, this was the first time a UBCV leader had reached out to citizens outside the Buddhists community, and it had a resounding impact, especially on the dissident community in Hanoi. Leading VCP veteran and dissident Hoang Minh Chinh was particularly inspired by Thích Quảng Độ’s proposals. Indeed, just before his death in 2008 of prostate cancer, this life-long atheist asked Thích Quảng Độ to convert him to Buddhism and be his master. At Hoang Minh Chinh’s funeral in Hanoi in February 2008, monks from the banned UBCV led the funeral rites, and situation unheard of in Communist Vietnam.

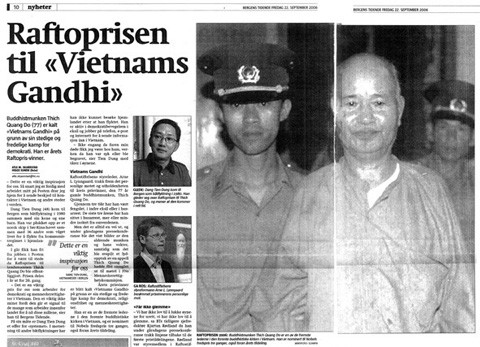

In 2006, the Rafto Foundation in Norway awarded

Thích Quảng Độthe

prestigious “Thorolf Rafto Memorial Prize”, honouring him for“his personal courage and

perseverance through three

decades of peaceful opposition against the communist regime in Vietnam, and as

a symbol for the growing democracy movement”. Vietnam refused to let Thích Quảng Độ travel to Norway to receive the Prize, despite repeated requests from

the Norwegian government. He asked Võ Văn Ái, UBCV Spokesman, to accept the

Prize on his behalf. Hanoi also turned down the request by Rafto Chairman, Arne

Lynngård to meet Thích Quảng Độ, and in March 2007 Security

Police arrested and interrogated Rafto’s Therese Jebsen as she came to Thanh

Minh Zen Monastery to hand Thích Quảng Độ the Award Diploma. In April 2006,

Thích Quảng Độ was awarded

the “Democracy Courage Tribute” by the World Movement for

Democracy along with dissident Hoàng Minh Chính at their 4th

Assembly in Istanbul.

In an interview on Radio Free Asia, speaking on the eve of the Communist Party’s 10th Congress in 2006, Thích Quảng Độ made the following comments:

“There will come a time when the authorities will be unable to silence all of the people all of the time. The moment will come when the people will rise up, like water bursting its banks. Together, 80 million Vietnamese will speak with one voice to demand democracy and human rights. The government will be unable to ignore their demands, and will have to face up to this reality. Then, the situation in Vietnam will be forced to change, and a democratic process will emerge”.

Thích Quảng Độ pledged the UBCV’s support to all peaceful movements for social justice and reform. In July 2007, he broke out of house arrest to speak at a demonstration of “Victims of Injustice”, a movement of farmers and peasants protesting official corruption and State confiscation of lands. This was the first time in 26 years he had addressed a crowd in public. It was also the first time in Communist Vietnam that such a prominent dissident had spoken out publicly for democracy and human rights. His words at the demonstration, surrounded by Security Police, were truly courageous:

“One single party cannot possibly represent more than 80 million Vietnamese people. We must have a multi-party system that gives the people wide representation. Freedom of expression is especially important, for without this freedom, how can people voice their grievances and express their opinions? First of all, we must settle the pressing questions of demanding justice, land rights and compensation for farmers. But after that, we must all work together for human rights, democracy and freedom. Everyone must do his part. We must work together until we succeed in winning pluralism and human rights for all the Vietnamese people. There can be no justice under a one-Party State”.

The State-controlled media launched a vicious campaign against Thích Quảng Độ after this, accusing him of “inciting people to oppose the government”, being a “gang leader with wicked designs”, seeking to “disturb public order” and oppose the Communist Party. He did not step down on his principles however, and launched a fund-raising campaign to support the “Victims of Injustice. In 2007, Thích Quảng Độ initiated a kind of “Grameen Bank”, providing micro-credit loans to the families of activists who had lost their means of subsistence because of their pro-democracy activities. These underground programmes are administered by more than 20 UBCV Provincial Representative Boards set up by Thích Quảng Độ since 2005 all over central and southern Vietnam to provide spiritual and material aid to the poor. The members of these UBCV Boards suffer persistent harassment, threats and interrogations, but are nevertheless realizing in concrete ways the UBCV’s ideals of compassion and salvation.

Thích Quảng Độ’s vision of democracy, articulated in his appeals and Open Letters for democracy, extends far beyond Vietnam’s frontiers. He believes in a peaceful and democratic Vietnam that will help engender peace and stability in Asia and the world, which can be achieved through solidarity and cooperation. In September 2007, during the brutal crackdown on Buddhist monks and civilians in Burma, Thích Quảng Độ wrote to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon calling for emergency UN action to stop the violence, and addressed a message of solidarity to the Burmese people. In March 2008, following the violent repression of demonstrations in Tibet, he sent a letter of solidarity to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, calling on China to open talks with the Tibetan leader, stressing that “only dialogue, never destruction, can open the way to a lasting solution in Tibet”. in September 2008, he wrote a letter of support to Buddhists in South Korea calling on the government to adopt anti-discrimination laws.

In December 2007, in the wake of widespread demonstrations staged by students and young people in Vietnam protesting China’s claims of sovereignty on the disputed Spratly and Paracel archipelagos, Thích Quảng Độ issued a Declaration calling on the Communist Party to abolish Article 4 of the Constitution (on the mastery of the Communist Party) and consult the Vietnamese population on this issue. The best way to safeguard Vietnam’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, he said, was to “pass the reins of power to the people in a society based on the separation of the three powers, multi-party democracy and the rule of law”. He added:

“Three million Communist Party members and a 500,000-strong army have neither the authority nor the power to defend the homeland by military means, nor sufficient prestige and courage to expand political and diplomatic efforts to mobilize international support in our defence… they need the full participation of the 85 million Vietnamese population and the support of the Vietnamese Diaspora worldwide”.

On 29th April 2008, as the Olympic Torch relay arrived in Saigon, Thích Quảng Độ attempted to join a protest organized by young Vietnamese. However, Police blocked all demonstrations. Thích Quảng Độ expressed his deception in an interview for Radio Free Asia:

“In Vietnam today, young Chinese can proudly parade their flag. Whereas young Vietnamese, the children of this land, whose ancestors shed their blood to preserve our territory, civilisation and identity, are forbidden by their own government, on their own soil, from expressing their national pride and protesting this indignity” (…). “We must reclaim our sovereignty on the Spratly and Paracel Islands. If 85 million Vietnamese remain silent and submissive, we will lose everything. Before we realize it, it will be too late. Vietnam has already lost part of the Nam Quan Border Pass to China and much more. If we do not resist, we could lose our sovereignty again. Not just for a few decades. Remember, in our history, we were under Chinese domination for 1,000 years”.

In August 2008, following the death of former Patriarch Thích Huyền Quang on 5 July 2008, Thích Quảng Độ became the Fifth Supreme Patriarch of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam. At his funeral on 11 July, Thích Quảng Độ pledged before his coffin to continue the movement for human rights and religious freedom.

Although he was never convicted of any crime – “I live in a legal limbo”, he said – Thích Quảng Độ remained under effective house arrest at the Thanh Minh Zen Monastery in Saigon until 2018. Despite harassments, threats and close Police surveillance, he continued to challenge the authorities on a range of human rights issues. In 2006, he urged the government to allow the creation of free trade unions to protect workers from growing abuses of labour rights under Hanoi’s policy of “đoi moi”, or economic liberalization. He launched a campaign of Civil Disobedience to protest environmentally-damaging Bauxite mining in the Central Highlands (2010); denounced trafficking of women and called for the release of detained women activists in Vietnam on the occasion of International Women’s Day; supported thousands of young people in Hanoi and Saigon demonstrating against Chinese encroachment on Vietnamese lands (2011); called for multi-party democracy and the abrogation of Article 4 of the Constitution on the political monopoly of the Communist Party during a government consultation on constitutional reform (2013); launched an appeal for a “broad-based movement for the democratisation of Vietnam” as the sole way to protect Vietnamese sovereignty (2014). These efforts brought him renewed interrogations, harassment and accusations of “violating national security”.

During his house arrest, many international figures who sought to visit Thích Quảng Độ were prevented from meeting him or subjected to Police harassments and interrogation. Police prevented the UN Special Rapporteur on Religious Intolerance Abdelfattah Amor from visiting him during a visit to Vietnam in 1998; Therese Jebsen, Director of the Rafto Foundation, was arrested as she attempted to hand him the Rafto Award Diploma on 15th March 2007; Italian Senator Marco Perduca and MEP Marco Pannella were prevented from boarding a plane in Phnom Penh to travel to Saigon to meet Thích Quảng Độ in December 2009; a Japanese monk who visited him in 2010 was fined $1,000 at the airport as he left Vietnam. Thor Halversson, President of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation was assaulted and detained by Police after he clandestinely filmed an interview with Thích Quảng Độ at the Thanh Minh Zen Monastery on 16th March 2010. Fortunately, he managed to send the video out of Vietnam. It was shown at the Oslo Freedom Forum in April 2010 under the title “Forbidden Faith in Vietnam”. It can be seen on Quê Me and IBIB’s website: www.queme.org.

Thích Quảng Độ’s international standing and symbolism as a leader of the movement for democracy and human rights led him to receive visits from many high-level diplomatic delegations, including the Ambassadors of the United Kingdom and the European Union (2005), the Ambassador of Australia (2012), successive US Ambassadors (2012, 2017) and the current US Ambassador Daniel J. Kritenbrink in June 2018. Other visits included US Assistant Secretary of State Tom Malinowsky (2015), US Congress members Chris Smith, Ed Royce, Loretta Sanchez, Matt Salmon, Alan Lowenthal (2005-2016), Consular officials from Germany and France, the UN Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Religion or Belief Heiner Bielefeldt (2014), democracy expert Larry Diamond and the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (2009, 2015, 2019).

In September 2018, Thích Quảng Độ was expelled from Thanh Minh Zen Monastery in Saigon by the monastery’s Superior monk Thich Thanh Minh, who said his presence caused “political and economic problems to the monastery”. Thích Quảng Độ left immediately, taking with him only a small suit-case with three monk’s robes. When his assistant came back later in the day to collect his sutras, books and belongings, Thích Thanh Minh had locked the staircase leading to his room and prevented the young monk from taking anything. For the next month, Thích Quảng Độ, then 91 years old, moved from one pagoda to another in Saigon with no permanent place to stay. In October 2018, he decided to go to his home village in Thái Bình province, northern Vietnam. On arriving there, however, he found himself under a new form of house arrest. He managed to escape from the North and came back to Saigon. He was to remain at the Tu Hieu Pagoda under close surveillance, deprived of the means to communicate independently and isolated from his close followers until his death on 22 February 2020.

International awards and support: Thích Quảng Độ was nominated 16 times for the Nobel Peace Prize. He was awarded the Rafto Memorial Prize by the Norwegian Rafto Foundation in 2006 for his role as a “unifying force” and a “symbol of the growing democracy movement in Vietnam”, the “Democracy Courage Tribute” by the World Movement for Democracy in 2006, and the “Homo Homini” Prize by the Czech Foundation People in Need 2003, under the auspices of the late President Vaclav Havel. In 2001 he received the Hellman-Hammet Award for persecuted writers from Human Rights Watch. Thích Quảng Độ was adopted by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience, and was an honorary member of PEN Clubs in Germany, France and Sweden.

Throughout his decades in detention, the international community ceaselessly appealed for Thích Quảng Độ’s release. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention pronounced his detention to be a violation of international law (Opinion 18/2005). The European Parliament and the US Congress adopted numerous Resolutions condemning his detention and demanding his unconditional release. In November 2015, 91 international personalities, including four Nobel Peace Prize laureates, signed a letter to US President Obama calling for his freedom. In April 2018, US Congressman Alan Lowenthal and Kristina Arriaga, Vice-President of the US Commission for International Religious Freedom adopted Thích Quảng Độ as a prisoner of conscience through the “Defending Freedoms Project” of the US Congress’ Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission.

On the news of his death on 22 February 2020, international personalities, religious leaders and admirers from all over the world sent messages mourning the passing of Thích Quảng Độ.

Thích Quảng Độ’s written works include : Deliverance from bondage (novel) – Under the eaves of the derelict pagoda (novel) – Buddhist legends (3 volumes) ; Translation of the “Dai Phuong Tien Phat Bao An” Sutra (7 volumes) – The essence of Primitive Buddhist thought ; The Essence of Hinayana thought ; The essence of Mahayana thought (trilogy) – War and Non-violence (translation into Vietnamese of the book by Radhakrishnan, former President of India) – Observations on the grave offences committed by the Vietnamese Communist Party against the Vietnamese people and against Buddhism (published by the International Buddhist Information Bureau, Paris, 1995); “Great Dictionary of Buddhist terminology”, a 6-volume, 8,000-page encyclopaedia of contemporary Buddhist terms containing 22,608 entries and 7 million words, written during his years in internal exile and prison. The manuscript was smuggled out and printed overseas; Prison Poems (published by the International Buddhist Information Bureau, Paris, 2007), a selection of some 400 poems written in exile and prison (without pen and paper, recorded by memory). In one of the poems describing his detention in solitary confinement, he wrote:

Thick darkness shrouds my prison cell,

In night’s deep silence, something fell

I strained to hear – then with a start,

Realised – it’s the beating of my heart.

Related articles from the international press:

New York Times (24 February 2020): Thich Quang Do, Defiant Rights Champion in Vietnam, Dies at 91

Washington Post (25 February 2020): Thich Quang Do, Vietnam dissident Buddhist monk dies at 91

Japan Times (23 February 2020): Vietnamese dissident monk who was a Nobel Prize nominee dies at 93 [AFP-JIJI]

Quê Me Quê Me: Action for democracy in Vietnam & Vietnam Committee on Human Rights

Quê Me Quê Me: Action for democracy in Vietnam & Vietnam Committee on Human Rights