GENEVA, 11 March 2019 (VCHR): As the UN Human Rights Committee meets at its 125th Session in Geneva to examine the periodic report of Vietnam on the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), one of the UN’s most important human rights instruments, the Vietnam Committee on Human Rights (VCHR) presented a “Shadow Report” documenting Vietnam’s systematic violations of fundamental freedoms and lack of compliance with its engagements to respect the civil and political liberties defined in the ICCPR.

Although Vietnam acceeded to the ICCPR in 1982 and has a binding obligation to submit regular reports to the UN Human Rights Committee, this is only the third time it has reported to the UN in 37 years. The first time was in 1989 and the second in 2002. The current report, which covers the period 2002-2017, is 14 years overdue.

“By delaying its reports over decades, Vietnam is not only failing to comply with UN reporting obligations, but also seriously undermining opportunities to strengthen protection of its citizens’ civil and political rights,” said VCHR President Võ Văn Ái. “Much of the information in the report is obsolete. Moreover, it denies glaring evidence of the government’s brutal assault on civil society, escalation of arbitrary arrests and long prison sentences for all those who simply advocate the rights enshrined in the ICCPR”.

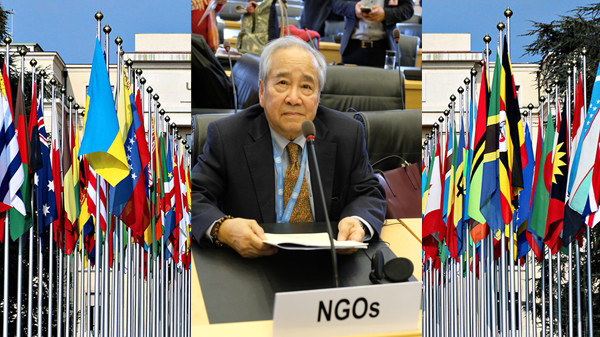

Testifying before the 18-member UN Committee of experts this morning, Võ Văn Ái presented VCHR’s report and made a number of key recommendations for reform. The Vietnamese government’s report was presented by Vice-Minister of Justice Nguyễn Khánh Ngọc and a delegation of 24 officials from Vietnam.

Civil and political rights are massively and systematically violated in Vietnam. Võ Văn Ái expressed particular concern on the use of broadly-defined “national security” provisions in the Criminal Code to implement political repression. “These vague, catch-all provisions are in fact a legal veneer to suppress human rights”, he told the Committee. “They make no distinction between violent acts and the legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of expression, and transform peaceful human rights advocates into criminals”.Virtually all domestic legislation, such as the 2015 Criminal Code, the Law on Religion and Belief, the Press Law, Cybersecurity Law, Law on Access to Information etc. contain clauses restricting human rights on the grounds of “ undermining national security” or “threatening the interests of the state,” in gross violation of the ICCPR.

National security provisions are routinely invoked to arrest, prosecute and imprison human rights defenders, bloggers, religious followers, civil society activists and all those who criticize the government or the Communist Party. In an unprecedently fierce crack-down on freedom of expression between January 2017 and February 2019, 117 civil society activists, including 23 women, were condemned to prison terms, several ranging from 13 to 20 years.

Most disturbingly, convictions of pro-democracy activists and government critics under Article 109 of the 2015 Criminal Codeon “actions aimed at overthrowing the people’s government” (which carries the death penalty) have “literally exploded”, said Võ Văn Ái. In 2018, 15 persons were sentenced under Article 109 and five others are awaiting trial, compared to six convictions in 2017 and two in 2016. In April 2018, six members of the “Brotherhood for Democracy” were sentenced to nine to 15 years in prison under Article 109 on charges of seeking to “build a regime of pluralism, multiparty and the separation of powers”.

“In the government’s view, advocating pluralism is synonymous with subversion, for it threatens the authority of the one-Party State”, said Võ Văn Ái. “In Vietnam, the survival of the Communist Party takes precedence over human rights.”

Unfair trials, systematic denial of legal defense, degrading detention conditions and ill-treatment of prisoners are routine in Vietnam, in violation of Article 14 of the ICCPR. The 2015 Criminal Procedures Code permits virtually unlimited pre-trial detention, prolonged incommunicado incarceration and secret trials for suspected “national security” offenders. Article 19 of the Criminal Code obliges lawyers to denounce their own clients if they are suspected of breaching national security.

Beatings, physical assaults, threats and intimidation, often by plain-clothed security officers or government-hired gangs and thugs, are widespread. Activists also face restrictions such as travel bans, confiscation of passports, denial or delays in passport applications, police surveillance, house arrest and the denial of citizenship rights.

The right to freedom of religion or belief is gravely violated. Under the Law on Belief and Religion, registration is mandatory, and no legal status is provided for groups not recognized by the state. Members of non-registered religious groups and communities such as the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV), Khmer Krom Buddhists, Protestant house churches, Hoa Hao, and Cao Dai have suffered increasing repression since the law came into effect in January 2018. UBCV leader Thích Quảng Độ remains under effective house arrest, deprived of access to communications. In August 2018, the Ministry of Defence called for increased Police surveillance of religious groups such as Falun Gong, and ordered “Force 47”, its brigade of cyber warriors, to post articles on the Internet denouncing their activities and warning people not to join them.

VCHR’s report also documented a whole range of abuses including restrictions on freedom of the press and Internet, notably the restrictive new Cybersecurity Law; violations of the right to freedom of association and assembly; escalation in the use of the death penalty; use of anti-demonstration regulations to quell protests on special economic zones in June 2018, in which at least 118 protesters were convicted; and abuses of the rights of ethnic and religious minorities..

“With no independent media, no free trade unions, no independent civil society, victims of human rights abuses have no mechanisms to express their grievances or protect their rights. 37 years after Vietnam’s accession to the ICCPR, its citizens are still deprived of their fundamental civil and political rights”, said Võ Văn Ái.

Contact : Penelope Faulkner : + 33 6 11 89 86 81 or Vo Tran Nhat : + 33 6 62 17 42 29

This post is also available in: French Vietnamese

Quê Me Quê Me: Action for democracy in Vietnam & Vietnam Committee on Human Rights

Quê Me Quê Me: Action for democracy in Vietnam & Vietnam Committee on Human Rights