Hanoi’s recent diplomatic efforts coincide with a brutal crackdown on free speech at home.

Over the past four months, Vietnam’s communist leaders have launched an unprecedented diplomatic offensive. President Truong Tan Sang and Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung have travelled to 10 countries including Russia, China, the U.S., the EU and beyond, to strengthen strategic partnerships, forge alliances and seek every opportunity to increase trade and investment to bolster the ailing economy of its one-party state.

Yet alongside this top-level diplomatic whirlwind, a very different offensive is taking place within Vietnam. In one of the most brutal crackdowns in a generation on freedom of expression, pro-democracy bloggers and online journalists have been beaten, harassed, interned in psychiatric institutions, arrested and condemned to sentences of up to life in prison for expressing critical views of the regime.

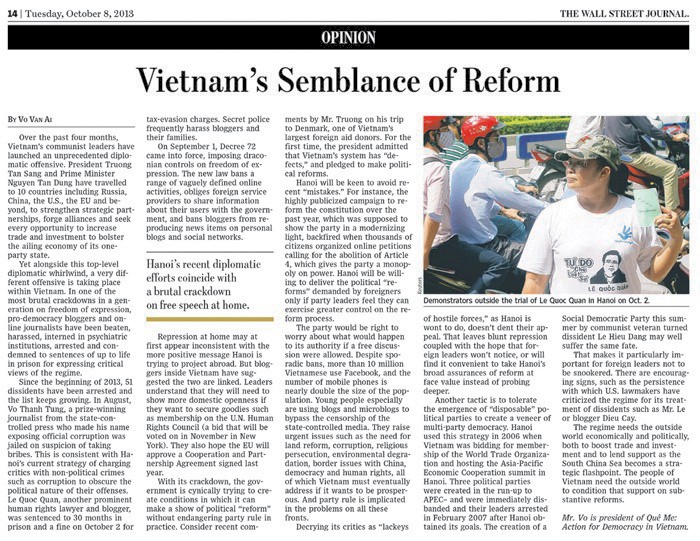

Since the beginning of 2013, 51 dissidents have been arrested and the list keeps growing. In August, Vo Thanh Tung, a prize-winning journalist from the state-controlled press who made his name exposing official corruption was jailed on suspicion of taking bribes. This is consistent with Hanoi’s current strategy of charging critics with non-political crimes such as corruption to obscure the political nature of their offenses. Le Quoc Quan, another prominent human rights lawyer and blogger, was sentenced to 30 months in prison and a fine on October 2 for tax-evasion charges. Secret police frequently harass bloggers and their families.

On September 1, Decree 72 came into force, imposing draconian controls on freedom of expression. The new law bans a range of vaguely defined online activities, obliges foreign service providers to share information about their users with the government, and bans bloggers from reproducing news items on personal blogs and social networks.

Repression at home may at first appear inconsistent with the more positive message Hanoi is trying to project abroad. But bloggers inside Vietnam have suggested the two are linked. Leaders understand that they will need to show more domestic openness if they want to secure goodies such as membership on the U.N. Human Rights Council (a bid that will be voted on in November in New York). They also hope the EU will approve a Cooperation and Partnership Agreement signed last year.

With its crackdown, the government is cynically trying to create conditions in which it can make a show of political “reform” without endangering party rule in practice. Consider recent comments by Mr. Truong on his trip to Denmark, one of Vietnam’s largest foreign aid donors. For the first time, the president admitted that Vietnam’s system has “defects,” and pledged to make political reforms.

Hanoi will be keen to avoid recent “mistakes.” For instance, the highly publicized campaign to reform the constitution over the past year, which was supposed to show the party in a modernizing light, backfired when thousands of citizens organized online petitions calling for the abolition of Article 4, which gives the party a monopoly on power. Hanoi will be willing to deliver the political “reforms” demanded by foreigners only if party leaders feel they can exercise greater control on the reform process.

The party would be right to worry about what would happen to its authority if a free discussion were allowed. Despite sporadic bans, more than 10 million Vietnamese use Facebook, and the number of mobile phones is nearly double the size of the population. Young people especially are using blogs and microblogs to bypass the censorship of the state-controlled media. They raise urgent issues such as the need for land reform, corruption, religious persecution, environmental degradation, border issues with China, democracy and human rights, all of which Vietnam must eventually address if it wants to be prosperous. And party rule is implicated in the problems on all these fronts.

Decrying its critics as “lackeys of hostile forces,” as Hanoi is wont to do, doesn’t dent their appeal. That leaves blunt repression coupled with the hope that foreign leaders won’t notice, or will find it convenient to take Hanoi’s broad assurances of reform at face value instead of probing deeper.

Another tactic is to tolerate the emergence of “disposable” political parties to create a veneer of multi-party democracy. Hanoi used this strategy in 2006 when Vietnam was bidding for membership of the World Trade Organization and hosting the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Hanoi. Three political parties were created in the run-up to APEC– and were immediately disbanded and their leaders arrested in February 2007 after Hanoi obtained its goals. The creation of a Social Democratic Party this summer by communist veteran turned dissident Le Hieu Dang may well suffer the same fate.

That makes it particularly important for foreign leaders not to be snookered. There are encouraging signs, such as the persistence with which U.S. lawmakers have criticized the regime for its treatment of dissidents such as Mr. Le or blogger Dieu Cay.

The regime needs the outside world economically and politically, both to boost trade and investment and to lend support as the South China Sea becomes a strategic flashpoint. The people of Vietnam need the outside world to condition that support on substantive reforms.

Mr. Vo Van Ai is president of Quê Me: Action for Democracy in Vietnam.

Quê Me Quê Me: Action for democracy in Vietnam & Vietnam Committee on Human Rights

Quê Me Quê Me: Action for democracy in Vietnam & Vietnam Committee on Human Rights